![]()

The factors affecting leech tension in a Windrush mainsail become critical on the race course.

In winds which are too light to lift one hull out of the water leech tension is not important. More ever, when the wind approaches hull hanging speed, leech tension becomes vital for both speed and pointing ability.

The Windrush sail is basically a dinghy design. That is, a full shape with the optimum power point at 50 percent, and not 40 percent as for many larger catamarans. The reason for this is the Windrush's lower power-to-weight ratio. The circular mast section also generates turbulence in the front part of the sail.

Here are some points that will be helpful in getting the best out of your Windrush.

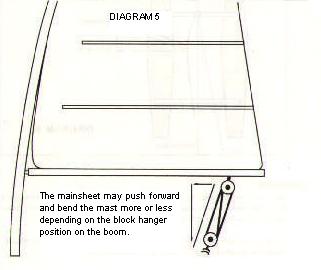

The effect of luff round

The luff round is the curvature built into the front of the sail to allow for mast bend. The amount required is directly proportional to the combined boat and crew weight. If you have insufficient luff round you will find yourself sheeting on harder and harder to stand your leach up so that you can point higher. The sail will become too flat before enough leech tension is achieved to give good pointing ability. You won't get the leech tension that you need with the power and fullness remaining in the sail.

If a sail is cut with little luff round for a light skipper and you take out a heavy crew member in medium conditions, the extra weight gives more counterbalance against the heeling force. Therefore, more sheet tension is required to hold up the leech. This in turn flattens and depowers the sail. You either lose power or pointing ability or both. This could show up as the need to locate the traveller closer to the centre than a correctly tuned boat in order to point as high.

The opposite effect will also be noticed. When the sail has too much luff round you may find it is too full for the all-up weight and cannot easily be flattened in heavy conditions. The boat will point well but there will be too much heeling force for the boat speed produced. It will feel as if the brakes are on. This could also show up as the need to set the traveller excessively far out.

Factors affecting leech tension

![]() DIAGRAM 1 . Forward push on battens

caused by triangulation

DIAGRAM 1 . Forward push on battens

caused by triangulation

Stronger battens will push forward against the mast harder. This pushing effect is created by that part of the batten which is in the roach of the sail. Consequently, the higher battens, (1, 2, 3 and 4) have more effect on mast bend that batten numbers 5, 6 and 7. (See diagram 1).

This effect is reduced in winds over 20mph because the compression forces in the mast are so high at these wind speeds that mast bend induced by battens becomes insignificant. (See diagram 2).

The idea that tying battens in tight produces fullness is incorrect.

If the battens are too light the leech will tend to hook in light winds simply because they don't have the strength to bend the mast. In heavy breezes the power point may tend to blow back. The power may tend to move forward in the sail in light winds when you apply the downhaul in an attempt to open the leech. This is not desirable.

Batten type also affects leech tension. The web-type batten, with wide ribs, spreads the batten pockets (especially at the leech end) and shortens the length of the sail. This usually tightens the leech and may cause hooking. (See diagram 3).

It will reduce the fullness in the sail, especially in the leech area. (See diagram 4). The flat part of the sail does not generate drive.

Symptoms noticed with the Web-type battens are: poor reaching speed, a tendency to being overpowered because of the tight leech, and poor light wind speed.

The power point in the batten affects the power point in the sail below wind speeds of 2mph. The further back the power in the batten (up to 50 percent) the more leech tension is needed to carry the extra drive.

The combination of a full sail and the power back (at 50 percent) requires more leech tension to hold the sail up. This especially noticeable in sloops where there should be more fullness up high and the drive further aft to reduce the power needed for the extra weight.

More sheet tension also gives more forestay tension, thus bending the mast below the hounds. In addition, a trapeze adds further to the compression below the hounds.

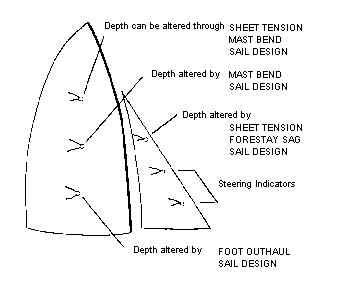

All of this leads to more mast bend below the hounds as the wind increases but adds very little to mast bend above the hounds. This is why more luff round must be cut into the lower half of the sail than the upper half. (See diagram 2).

This effect is less obvious with heavier mast sections and more pronounced with lighter sections.

Sail cloth choice has been limited for racing since the early 90's, when the Windrush class settled on one sail design, supplied by the manufacturer. This design has more roach in the main and uses a reinforced Mylar sail cloth, which gives a live of 5-7 seasons.

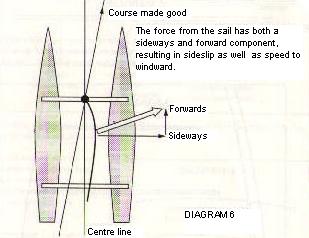

This is because the sail produces a force which can be resolved into a forwards and a sideways component. The closer the sail is sheeted to the centre line and the tighter the leech the greater the sideslip. but it is worthwhile to achieve pointing ability.

DIAGRAM 6. The force from the sail has both a sideways and a forward component leading to sideslip as well as speed to windward.

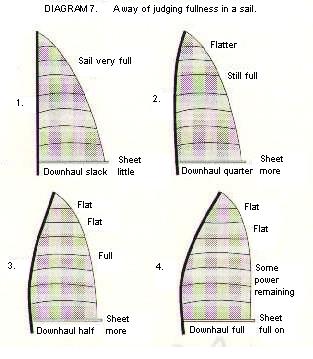

Conclusion: One way of judging a sail by gradually increasing sheet and downhaul tension with the boat on the beach. As the mast bends, the sail should flatten progressively from the top, down to batten number 4. (See diagram 7).

On the race course the correct balance of leech tension and sail shape is critical. Hopefully, the ideas here will help you to achieve this.

DIAGRAM 7. A way of judging fullness in a sail.

Progressive flattening of the battens from the top of the sail down to the batten no.4 as mainsheet and downhaul tensions are increased. This only applies in a static position on the beach. When sailing the wind will induce some fullness. In this test a mis-match of luff round and batten weight can cause batten no. 4 to flatten before no.s 1,2 or 3.

A yacht with a full sail is like a car in low gear ( like a tractor)

A yacht with a flat sail is like a car in top gear

Having done all this, don't be tempted to continually keep fiddling with bits and pieces. Go out and get plenty of practice and experience. Boat handling skills are paramount to performance.

When starting to assess sails, it is important to remove the guess work by using any reliable indicators available. In the case of sails the best indicators are Telltales and Leech Ribbons.

We need indicators to feedback information in order to evaluate our performances. e.g. The speedo in your car. Thermostat on the heater. A second boat to compare speed.

Telltales and leech ribbons feed us information about the way air travels across our sails.

They can give us information about:

The way we steer our boat

How hard / soft to sheet the sails

How deep / flat the sails are

How much twist we should sail with

Correct placement of the telltails and leech ribbons is essential for reliable feed back, in order to maximise the performance of the sail and rig.

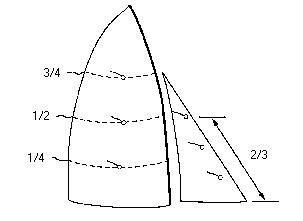

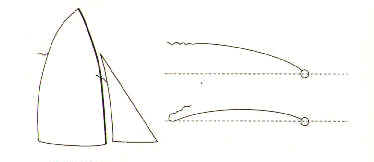

In general the leech ribbons will indicate if the sails are too tight or too loose and the telltales will indicate if the sails are too full or too flat for any given wind strength.

To observe and assess the telltails is quite simple.

Firstly we assume you are now using the correct sheet tensions, because you have been observing the leech ribbons.

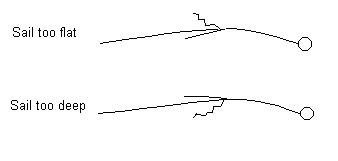

In general, if the windward telltails are stalled,the sail is too deep and conversely if the leeward telltales stall the sail is too flat.

THE SECRET TO USING THE SAIL INDICATORS IS REMEMBERING TO OBSERVE AND ACCURATELY ASSESS WHAT THEY ARE DOING AND INDICATING.

The optimum setting for the ribbons on the leech, are a stall / flow ratio of 50 / 50. Hence, if you watch the leech for a period of time , say one minute and the ribbons only disappear for ten seconds then the sail is under sheeted and has too much twist.

The boat with a sail sheeted on this way will probably be under powered and lack the ability to sail high.

REMEDY: Pull the sheet on harder.

If the leech ribbons can only been seen for ten seconds, chances are the sail is stalled. In this case the boat may be point high, but will generally lack speed through the water.

REMEDY: Ease the sheet tension and hence allow the sail to twist more.

The only ribbon to watch to check the above is the top ¾ ribbons. It is this point that the sail twists the greatest amount.

REMEMBER: The closer to the centreline a sail is sheeted, the higher or closer to the wind the boat will sail, provided the airflow does not separate from the sail, i.e. stall out.

NOW GO OUT AND ENJOY SAILING!

This document was produced in the

interests of better sailing, by:

The Windrush Catamaran Association of

Western Australia and Windrush Catamarans

Re-produced by:

Windrush

and Prindle Catamaran Association of New South Wales Inc.